Whether you like them fresh or from a can, I hope you enjoyed your cranberries yesterday! Get ready to cozy up and take a step back in time with me to last spring when I went north to Troy, Maine to paddle around Carlton Pond.

The best way to experience Carlton Bog, also called Carlton Pond, is by boat, preferably in late spring. In mid-May in Maine, the bugs aren’t yet out in full force, the air is warm, and the gray landscape is filling in with new vibrant colors everyday. The timing of our visit to Carlton Bog was strategic. Not for the enjoyment of the mild weather on the cusp of summer, but to spot a very special bird.

Carlton Pond is one of the few areas in the State of Maine which provides nesting habitat for Black Terns. They are a state-endangered species, and have been monitored by the state, federal biologists, and researchers since 1990 in an attempt to better determine the species’ population status (USFWS).

Although less common in Maine, Black Terns are a fairly widespread species throughout North America and Europe during the breeding season and winter in Central America, South America and Africa. According to eBird, Black Terns are most frequently observed between May and August around Troy, Maine. One reason why Carlton Bog is so attractive to Black Terns is because this site is also a designated Waterfowl Production Area.

Waterfowl production areas are wetlands (and surrounding uplands) that provide breeding, resting, and nesting habitat for waterfowl, shorebirds, water birds, and other wildlife. About 95 percent of the Nation’s Waterfowl Production Areas occur in the prairie potholes region of the Midwest (USFWS 2007). More on this later. Unique to the northeast, Carlton Pond WPA is the only Waterfowl Production Area in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s North Atlantic-Appalachian Region (Carlton Pond WPA). The creation of Carlton Pond WPA was authorized by administrative action on July 15, 1964, and the WPA was officially established one year later. The 1,068-acre Carlton Pond WPA consists of wetlands, forest, and of course the pond itself which is 285-acres of open water.

The hydrology defining Carlton Pond, however, is relatively recent. In 1850, a rock dam was built near the site to power a local sawmill southwest of the pond. This changed the natural flow of Carlton Stream and presumably created a widening and deepening of the existing water channel. Today, Carlton Pond is quite shallow (most of the open water is less than 8-feet deep) which creates perfect conditions for marsh and bog vegetation to take hold.

Unfortunately, it seemed as though we were too eager in our visit because we arrived before the Black Terns had come back on spring migration. Instead, we were absolutely delighted to be treated by the aerial displays of Wilson’s Snipes, the males performing a fast, zigzagging flight pattern around the pond. We would track them for as long as we could while they were in the air until they fluttered back down into the bog where they would disappear from sight. The only indication that they would be back up in the air was the unusual “winnowing” sound made when their tail feathers are fanned out (listen here). Researchers have done wind tunnel tests with Wilson’s Snipe feathers to try and duplicate this sound. They found that the outermost tail feathers, or rectrices, generate the sound, which apparently happens at airspeeds of about 25 miles per hour (allaboutbirds.org).

Wilson Snipes were not the only birds attracting our attention that day. In the spring, male birds are especially territorial. They can be seen performing vibrant displays of bravado, while singing all the greatest hits of their species in a melodious effort to establish nesting sites and to attract potential mates. These songs, often complex and varied, not only serve to entice females, but also to communicate with rival males nearby. Some songbirds, like the Red-winged Blackbird, are especially aggressive and are not afraid to chase down large raptors or other intruders that may threaten their territory. Their boldness can be quite remarkable, as they transform from beautiful singers into fierce defenders when faced with a potential challenge. This dynamic interplay of courtship and confrontation creates a lively atmosphere in the natural world during mating season.

Aside from birds, our eyes were drawn to the many colorful flowering plants. My favorites, rhodora and cotton grass, make a whimsical confetti effect of pink and white amongst the vibrant greens of the tamaracks and leather leaf that surround them. This time of year, as spring unfolds, the yellow bulbs of water lilies are just starting to emerge from beneath the water, their bright color hinting at the beauty that will soon blossom across the surface of the bog.

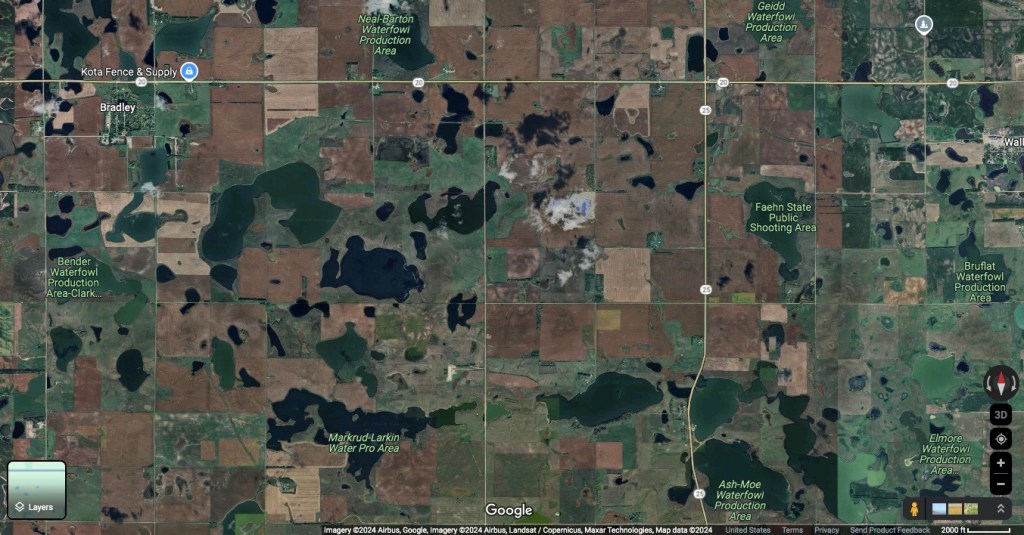

A quick note on prairie potholes. As mentioned earlier, they are found in the midwestern United States. Though not a bog, they share some similar characteristics: both were formed by recent glaciation, they are isolated wetlands, and they provide important wildlife habitat. Unlike bogs in the northeast, however, prairie potholes make up an entire region in the Great Plains and are easily seen in aerial imagery in places like South Dakota.

Suffice it to say, birds love it here. There is an incredible diversity of shorebirds, waterfowl, songbirds, and raptors that breed in the Prairie Pothole Region, or use it as a stopover site to fuel up on their way to and from the arctic and other northern breeding grounds (National Wildlife Federation). I was also lucky enough this spring to see this astonishing ecosystem first hand. After our failed attempt to see Black Terns at Carlton Bog, I had no idea how quickly my luck would change. Just two weeks later, I was in eastern South Dakota on a research trip for work and could not believe just how many birds were in these potholes. So many birds I had never seen before, all in one place, and only for a short time. It was a birder’s paradise. One species that would stick around for the remainder of the breeding season though, was the Black Tern! And there was no shortage of them either. Circling around the potholes in flight and gracefully skimming the water for food, I couldn’t believe how fortunate I was to be standing on the side of the road in your classic midwestern farming landscape watching the birds that eluded me just two weeks ago. They paid no mind to us and I was grateful for the view.

To say the prairie potholes region ignited a spark of joy in me is an understatement. These extraordinary ecosystems are directly intertwined with the “breadbasket” of America and I plan to delve deeper into their significance and beauty in the near future with a special guest contributor and dear friend who shares my passion for wetlands. Together, we aim to highlight the importance of preserving these habitats and the role they play in our ecosystem. Stay tuned, friends, as we embark on this exciting journey to uncover the wonders of the prairie potholes!